Our late Chairmen Emeriti Lew Burridge and Felix Smith have delighted us with a new chapter to our CAT History Project with each edition of the Bulletin. We have condensed this effort into one volume here.

We open the study with information depicting both the support and opposition to General Chennault and Whiting Willauer’s mission to support “free China” in its rehabilitation from decades of resistance to Japanese aggression and resistance to Russian and CHICOM attempts to dominate and separate China from the West. General Chennault’s long and very intimate association with China and Chinese at every level before his retirement from the 14th Air Force gave substance to his views that the United States must do all in its power to support freedom in China as a deterrent to the spread of communism throughout Asia.

While his efforts received opposition from powerful people, both in China and in the USA, he had some determined and influential friends in both countries working behind the scenes, as well as publicly, in support of his proposals for an aviation answer to some of the needs that were eroding China’s ability to survive. Chief among these friends was Thomas “Tommy the Cork” Corcoran, a Washington attorney and an FDR favorite in his administration.

Thus, our review of CAT’s birth begins . . .

General Chennault’s history with China is well known, but that of the Corcorans and Whitey Willauer is less so.

Tom Corcoran’s brother, David, was President of China Defense Supplies (CDS), organized by Tom under the order of President Roosevelt. CDS was chaired by T. V. Soong, China’s Foreign Minister and brother of Madam Chiang Kai Shek.

CDS was charged to aid the formation of the American Volunteer Group (AVG) under Chennault. CDS was later expanded to be the Chinese Government’s agency for bolstering aid in support of the battle against Japanese aggression in China. Whitey Willauer had been a schoolmate at Exeter of W. H. Corcoran, the third brother, and knew the family well. In contact with CDS from October 1942 to late 1944, Willauer stated that he had spent two-thirds of his time in China and the balance in Washington DC expediting “problems concerning the overall Chinese war effort.” In 1944 Willauer was appointed Director for the Far East and Special Territories Abroad of the U.S. Foreign Economic Administration. His territories included China, Japan, Formosa, Korea and Southeast Asia. In 1945 FDR ordered him to the Philippines to “do what he could to restore the civilian economy of the Philippines.”

Prior to that, Willauer had worked on support for Chennault’s 14th Air Force through China’s Ministry of Communications. He also helped pioneer the Hump Airlift from India to China – the only lifeline free from Japanese occupation. As a result of these actions, he became a close friend of Chennault. He once stated “It seemed a natural thing for us, with our mutual love for China, to return there together to help in China’s reconstruction.” With Chennault, Willauer gave informal advice and support to UNRRA/CNRRA, the official U.N. Agencies for China assistance. It was recognized early on that there was an essential need for additional airlift capacity in connection with these programs as there were only thirty civilian planes then in China and not all would be available for the mission. Chennault returned to China from the U.S. in late 1945 and estimated that about 300 planes would be required to carry the ton/mileage needed to meet the cargo requirements identified by UNNRA. When returning to Washington, Chennault and Willauer found that Pan American Airways (PAA) knew of and had “declared war” on their plan to establish a Chinese operation, which PAA considered competitive to their modest 20 percent interest in the China National Aviation Corporation (CNAC), a PAA/Chinese joint venture. PAA had obtained some well-positioned supporters in the U.S. to assist it in killing any Chennault/Willauer entry into the China aviation market.

At the same time, Chennault encountered resistance to the plan from certain sectors of the Chinese government and some political activists. Willauer later pointed out “. . . it was largely due to the great trust, particularity of Generalissimo Chiang Kai Shek and T. V. Soong, that in 1946 we obtained a ‘personal contract’ between the Chinese Government and Chennault and me to operate a relief airline . . .”

UNRRA agreed to loan CNRRA the funds required by Chennault and Willauer to purchase surplus U.S. military aircraft. The CNRRA loan had to be repaid and carried interest at 10 percent compounded annually. This then left Chennault/Willauer with the job of raising an additional $250,000 needed for working capital. Negotiations with Bob Prescot, President of the Flying Tiger Cargo Airline seemed promising, until . . . Prescot had sent his brother to Shanghai to negotiate, but during a stopover in Manila he was shot to death, as an innocent bystander, in the lobby of the Manila Hotel. In spite of every effort made by Corcoran and Chennault/Willauer, this tragedy “dried up” any early prospects for U.S. funding.

As the need for operating capital was now critical, Willauer, through a close Chinese friend formerly with the Chinese Ministry of Communications, Dr. Wang Wen San, succeeded in interesting a Chinese group of investors to make Chennault/Willauer a loan of $250,000 for eighteen months at high interest rates secured by a 40 percent interest in the equity of the new airline.

While U.S. supporters were appalled by the terms of the loan, it was repaid early. The Chinese lenders also proved to be valuable allies in addressing the infant airline’s salary problems and in beating back attacks from those, such as CNAC, that feared CNRRA Air Transport (CAT) competition. [CNAC/PAA and CAT later became good friends.]

Still backed strongly by Chiang Kai Shek, T. V. Soong, the Corcoran Group and other supportive figures in the U.S. and China, operations under the Chinese flag became official on October 25, 1946.

CAT was restricted under its franchise, however, to carrying only UNRRA/CNRRA cargoes destined for the rehabilitation of China’s interior cities and facilities not easily reached by other forms of the disrupted post-war transportation systems – a difficult pregnancy, but at last the baby was born.

With the franchise signed, basic administrative staff in place, flight crews on standby, operating capital in hand, and CNRRA cargoes enroute from the USA, a “home base” needed attention. At one time Canton’s southern airport seemed most desirable with its local facilities, unobstructed flight path, close proximity to Hong Kong’s port with substantial aircraft service and maintenance facilities, plus a more temperate climate.

However, CNRRA Headquarters was in Shanghai. Most of the relief UNRRA cargoes were destined for Northeast, East and Central China; shipping time and costs would be lower to Shanghai than to HK-Canton; and all other carriers were now based there. So Shanghai became the final choice. By then a CAT office had been set up in Shanghai at 17 the Bund. It was not an easy decision even though CAT administrative and business offices were there for initial organization.

Shanghai had four airports that could be made suitable for air cargo operations. However, the best three were already assigned to others: Ta Shang to the Chinese Air Force, Kiang Wan to CNAC, and Lung Hwa to the 14th Air Force. So the fourth, Hung Jao, was assigned to CAT. Hung Jao, a fighter strip, needed substantial work since being abandoned by the Japanese.

Security was also a serious problem. Weather facilities were absent, as were communication facilities and maintenance shops. But it did give CAT a degree of independence, which was welcomed. Work to upgrade the facility was underway even before the franchise was signed, but financing for it became a larger than anticipated problem.

The company went again to Corcoran to raise a second $250,000 needed for improving facilities and equipment to ensure a safe, efficient operation. It was a tough assignment with great urgency, but Corcoran accomplished it by forming a group of investors named Rio Cathay. The terms required the surrender of part of Chennault and Willauer’s equity in the airline. Willauer, in his papers, said he was appalled by this, not for himself, but he insisted that Chennault’s equity not fall under 30 percent.

The deal was made, and CAT sent its flight crews to Manila and Hawaii to pick up its first five C-47 and fourteen C-46 aircraft.

With the UNRRA / CNRRA agreement signed on October 25, 1946, there was an assumption by CNRRA that CAT would “get moving” immediately on the airlift of food and medical needs to areas isolated (by “Reds”) from essential supplies. Very restricted by funding, Chennault also knew that CNRRA officials had little knowledge of the technical facilities and personnel requirements, funding and time it would take to support the dispatch of the first relief flight. In anticipation of this, Chennault had chosen to recruit AVG associates, military pilots and technicians who had China experience and had proved themselves proficient in performing under the minimal and restrictive operating conditions during WWII and post-war China.

AVG Ace Joe Rosbert, and in DCA, Doreen Lonberg, also assisted in recruiting former AVG and Flying Tiger Lines pilots in the USA. These pilots were Catfish Raine, Bus Loane, and Bob Conrath. (CAT’s original technical team was Ken Buchanan, Chief Pilot; H.L. Richardson, Chief Engineer; Clyde Farnsworth, PR Officer; and Dr. Tom Gentry, Medical Director. All former Chennault men.)

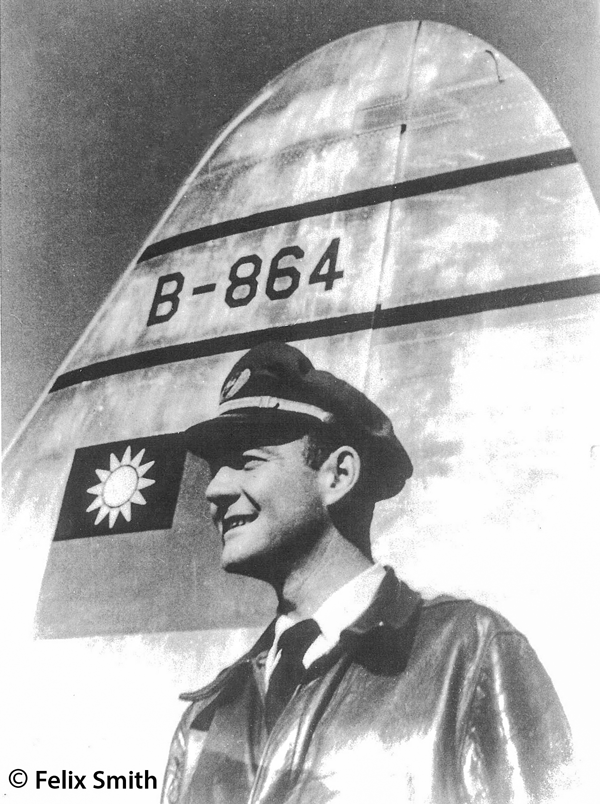

For Operations his choice was Colonels Richard Wise and Charles Hunter who were granted detached service from the 14th Air Force. For recruiting pilots they were greatly assisted by AVG Ace Dick Rossi. Rossi had come back to China to join GCAC (Great China Aviation Corp.) which was negotiating for a franchise in Canton. He recruited Tsingtao-based Marine Corps veterans Lew Burridge and Var Green, and Naval Air Corps veterans Bill Hobbs and Weldon Bigony for GCAC. But when that corporation failed in obtaining an operating license the pilots were put on standby in Shanghai (with CNAC veteran Felix Smith) to await CAT employment when CAT became licensed for CNRRA operations.

Shortly after Christmas 1946, CNRRA confirmed that the five C-47s at Clark Field in the Philippines and fourteen C-46s in Hawaii were available for pick-up. CAT activated the pilots who had been on “standby” since November 1946. Chennault selected Marine pilots Lew Burridge and Var Green, Air Force pilots Stu Dew and Paul Holden (after serving General Marshall), and Naval Air Corps pilots Weldon Bigony and Bill Hobbs. Thanks to the work of COL Dick Wise and Dick Rossi, these crews were ready for departure to Clark Field in the Philippines on military transport from Shanghai.

Chennault gave Lew Burridge $500 to cover expenses for the trip with a request that they return any amount that could be saved. The CAT group arrived at Clark Field still in military uniforms without insignia as there was no time or money to buy civilian clothes or CAT uniforms.

They were well received at Clark Field, but found than none of the dozens of surplus U.S. Army planes there were airworthy. With the help of a few “moonlighting” Air Force technicians, they selected five with lowest airframe and engine time. This plan soon required that two of the five C-47s be cannibalized for parts. Working with informal assistance from the Air Force, they created three flyable C-47s. The planes were examined by Philippine Airlines and certified to meet U.S. standards. They flew to Canton on January 25th with minimal fuel due to exhausted funds and cabled their Shanghai office to arrange re-fueling credit with the Standard Vacuum Oil Company (SVOC). They were told that SVOC, Hong Kong, would assist, so they landed there on January 26th after aborting the first CNRRA load to Kweilin due to severe weather. (Three CNAC planes and one Central Air Transport Corporation, CATC, plane had crashed at Shanghai on December 25th due to dense fog.) At arrival in Hong Kong the crew encountered considerable negotiations with officials because of the lack of recognizable identification on the planes and were held up for necessary clearance and refueling. In spite of the dismal and minimal weather reports, the first flight took off and landed at Lung Hwa and then went on to CAT’s base at Hung-Jao on January 26, 1947.

On January 31st, pilots Frank Hughes and Doug Smith, with UNRRA cargo, a Jeep, and General Chennault aboard, made CAT’s first commercial flight from Shanghai to Canton. CAT was at last in business!

Later, Var Green flew a CNRRA relief flight from Shanghai to Peking. On the C-47 pre-flight run-up in Peking, prior to the flight continuing to Taiyuan, a leaking primer line caught fire and the plane was destroyed on the ground there. The two remaining C-47s continued a very busy relief schedule without further incident.

While Burridge and his men overcame their initial challenges in the Philippines, similar frustrations occurred in Hawaii. For a short period, COL Oliver Clayton was Acting Operations Manager and COL Bill Richardson was Chief Engineer. Acting Chief Pilot Dick Rossi and CNAC veteran Felix Smith were dispatched to Hawaii via military transport, expecting to find CAT’s 17 C-46s in fly-away condition, but when they got to Wheeler Field on Oahu, they saw fuselages encased in heavy cosmoline, devoid of engines.

Recently demobilized USN Supply Officer Bob Lee (Chennault’s son-in-law) explained what any competent supply officer knows: A war-surplus airplane is kept in perfect condition by pickling the hull and moving its engines and accessories to a corrosive-free facility. Bill Freeman, a former U.S. Army captain in the CBI Theater, was dispatched to Hawaii to manage the huge maintenance challenges with Susan Pollock (Sue Buol Hacker) as his secretary.

The lead mechanic was Johnny Glass with Joe Melger and Ronald (Doc) Lewis. The Communications Officer was former AVG and 14th AF COL John Williams. They were followed by Army Air Corps Engineering Officer Oliver Clayton, whose principal assignment was the purchase of spare aircraft parts which were on sale at rock-bottom prices from Oahu’s numerous war-surplus outlets.

From January to March 1947, CAT’s two C-47’s were kept busy surveying potential landing fields near cities and towns scheduled for food and medical aid — most of which were surrounded and isolated by Communist forces. Many air fields were poorly constructed and suitable only for Japanese light fighter aircraft. Except for major cities (Peiping, Shanghai, Tsingtao, Canton, Kweilin, Chungking, Nanking, Chengdu) ground facilities were almost non-existent. The CAF (CATC) and CNAC had minimum fueling and communications facilities, but CAT found it was not welcome to share them. So CAT had to move quickly to secure landing permits and develop its own essential support services for the large scale operations necessary to meet CNRRA expectations after the CAT UNRRA C-46 fleet began to arrive from Hawaii in March.

Lew Burridge, Harry Cockrell and Bill Freeman were appointed Area Managers with headquarters at bases in Tsingtao, Canton, and Peiping. Joe Rosbert headed overall operations from CAT’s main base at Hungjao, Shanghai.

Due to CATC and CNAC opposition to CAT services, constant liaison with the Chinese Government, critical to break such deadlocks, was undertaken by General Chennault, Dr. Wang Wen San, Henry Yuan and David Tseng . . . China’s history up to 1947 provided a challenge for the CAT operations.

In 1945 there was an agreement in place between Chiang Kai-Shek and Stalin in which China would, at the end of the war, cede control of the Japanese occupied industrialized Manchuria to Russia in exchange for a pledge by Stalin to withhold aid to General Mao’s communist forces.

Stalin reneged on his pledge. Russia quickly plundered Manchurian civilian and industrial assets and materials, while at the same time arming Mao’s forces (as they moved north) with captured Japanese equipment. Russia opened 16 training installations and gave two ports to Mao. The Japanese war “spoils” given Mao by Russia included 900 planes (w/o pilots), 760 tanks, 3,700 artillery pieces, 12,000 machine guns, armored vehicles, anti-aircraft pieces, and thousands of captured Japanese and Korean soldiers and laborers.

This action by Stalin in 1945-1946 disrupted a smooth recovery and reoccupation of Chinese territory by China’s Nationalists and alarmed Washington, causing the U.S. 7thFleet to be moved into Shanghai and Tsingtao in October 1945. This action also brought CAT’s Marine pilots to Tsingtao, Tientsin and Peiping. All Marine bomber and fighter pilots were converted to fly transports (VMR-153) with Tsingtao as their main airbase. Other Air Force, Navy and civilian pilots recruited in China were also familiar with most of the operating area. Thus CAT had very experienced personnel in North China as it took on military support and relief services for the areas isolated by communist forces as they moved North.

Stationed “back home” in Tsingtao, CAT’s Marine pilots had considerable support, such as maintenance, parts, GCA operations and social activity, from USMC friends across the field from CAT’s headquarters.

U.S. concerns over the deterioration of China’s effectiveness in recovering and controlling its areas North of the Yangtse River and Manchuria caused, in December 1945, the formation of a mission led by General George Marshall (Stu Dew was his pilot) to broker a ceasefire and a coalition government. Marshall ordered Chiang Kai-Shek to stop all advances against the communists for 45 days during his negotiations between the two parties. On January 3, 1947, Marshall left China with his mission failed, and Chiang Kai-Shek resumed defensive/offensive action against the now Russian-supported communist forces.

CAT, however, continued to receive considerable support from former U.S. Military Attaché Col. David Barett, Tsingtao’s U.S. Consul General Robert Strong and the local Chinese Military Commander, General Ting Shih-pan. Chiang Kai-Shek’s Northern forces, under the command of General Wei Li Kuang, ignored Chiang Kai-Shek’s order to create a strong front line to force the communists to stay North of Peiping. General Wei chose instead to abandon the countryside and retreat to the cities. Communist forces, then 1.3 million, with increasing control of the countryside, plundered farmers (to pay for Russian arms) and impressed conquered males into their armed forces.

With Manchuria in the process of evacuation, Peiping coming under attack and nearly all surface transportation in the North disrupted, CAT support to refugees from Manchuria and isolated cities was a critical factor if Nationalist China’s defense plans, public morale, and reasonable security was to be maintained. General Chennault welcomed this challenge and all operations were put on a 24 hour daily schedule to meet the demands. CAT performed admirably under the worst of conditions and saved many thousands of lives.

The CAT contract with CNRRA called for the exclusive use of twelve CAT aircraft at rates 20 percent lower than those of CNAC and CATC (later reduced to 33½ percent lower). This meant that the CAT flights, after deliveries inland of CNRRA shipments, returned empty. In April 1947 the CNRRA contract was amended to make CAT inbound flights available for the airlift needs of other government agencies including the Chinese Postal Administration. By September 1947 most restrictions on the carriage of cargo and passengers were eliminated.

As inland cities became isolated, one by one, by the Communists, CAT operations from its coastal supply points faced near endless requests for the transport of vital needs of the many communities cut off from their farms and local supply sources. Their populations became bloated by refugees escaping communist capture and occupation. The key ports for CAT operations were Shanghai, Tsingtao, Tientsin and Peiping in the East, and Canton in the South. After the fall of Peiping and Tientsin, Tsingtao became the center for CAT’s operations supplying Taiyuan, the last major city north of the Yellow River. These flights benefited by requiring only half the time as those originating in Shanghai.

The growth of CAT, even with limited equipment, was dramatic, resulting in CAT becoming the world’s largest cargo airline within its first 18 months of operation.

CAT’s tonnage records during its three years of support to China’s cities was beset with challenges. As city after city lost its airstrip, emergency substitutes were built. In Peiping it was at the “Temples of Heaven”; in Tientsin, a sports area between city walls; in Wei Hsien, the city market and tennis courts. In other cases, any firm ground was used. In Taiyuan eleven strips ringed the city as communists shelled one area after another. Finally a short strip was turned into the mountainside to shelter at least part of the flights in and out. After landings were impossible, CAT crews then resorted to airdrops until the final full occupation of cities by communist forces.

To maximize available space, CAT’s C-46s maintained a cargo configuration with passengers “tucked in” whenever space free of cargo was available. In addition to Chinese government passengers, CAT became the principal carrier for correspondents, missionaries, diplomats and local officials during the final days of its support to evacuations.

The “Marshall Mission” left China in January 1947, ending coalition attempts.

Wei Hsien was captured in June 1947, a few days after stranded CAT pilots were rescued.

In 1948 Linfen fell in March and Manchuria in November. During the reinforcement of the defenders of Mukden, our first casualties occurred – pilot, Tud Tarbet; copilot, Har Yung-shing; radio operator, Chan Wing-king; along with sixteen Chinese soldiers.

CAT opened a Cessna 195 operation in Northwest China for communications between Chinese Muslim anti-communist warlords Ma Pu-fang and Ma Hung-kwei on July 19, 1948. USMC veteran Eddie Norwich was killed flying a Cessna when caught in a dust storm in the Lanchow area.

In January 1949, a CAT group in Tsingtao moved to strike over threats by communist agitators, but it was overturned by loyal employees and USMC guards. Lew Burridge’s treatise on the defense of Shantung Peninsula appeared in the U.S. Congressional Record.

In 1949 Hsuchow fell in January, Taiyuan in April, and Hankow and Tsingtao in May. This left CAT flying “round the clock” as China’s only remaining airline after CNAC/CATC defections.

Shanghai was surrounded in late May and Lunghua and HungJao airports were occupied. CAT had sent a C-46 to the Nanking area to witness whether or not the Red 8th Army could cross the Yangtze (a strategic “Indian Sign” in the Civil War.) The crossing of the Yangtze was supposed to forebode the eventual fall of the entire mainland of China.

Felix Smith flew this one with Dave Lampard in the right seat while Whitey Willauer and Bob Rousselot watched them depart Shanghai. They saw the Red infantry crossing in small boats without apparent opposition from Nationalist troops, nor did they see any artillery fire. Though they flew low, about 800 feet, the Red troops didn’t shoot at them. It’s arguable that CAT was the first pro-Nationalist organization to learn of the crossing of the Yangtze.

All CAT personnel and equipment were moved to Canton and Hong Kong. CAT’s LSTs evacuated heavy maintenance equipment from Shanghai to Canton. The sea borne heavy maintenance facility (propeller shop, magnefluxing tanks, parachute loft, hydraulic shop, electrical instrument shops) was sea-minded Willauer’s brainstorm. Given this WWII veteran LST, the Narcissus (a converted WWII PT boat), and Chinese barge (Buddha), CAT designated Whitey Willauer “Admiral of the CAT Fleet” in fun, but Whitey was quite proud of the award.

One C-46 remained in Shanghai at Kiangwan housing Lew Burridge, Var Green, Earl Willoughey and Pete Dorrance (who remained as CAT caretaker for weeks after communist occupation). On May 15, 1949, Lew Burridge opened Amoy as a transit point for the final evacuation of Nationalist Government personnel and assets from Chengtu to Taiwan.

During CAT’s temporary evacuation of persons from the last-standing Nationalist cities to Hainan Island, including Mengtze, CAT also evacuated the Bank of China’s silver to Hong Kong for surface transit to Taiwan.

The diversity of CAT cargoes was seldom equaled. In addition to relief and military supplies, CAT carried cattle from Tsingtao to Yunan, tobacco from Wei Hsien to Tsingtao, wool from Lanchow to Peiping/Tientsin (in competition with transport by camels), cotton from Tsinan to Tsingtao, 50,000 doses of cholera serum from Shanghai to Huangcha, Nationalist currency from Shanghai to Chungking, silver dollars from Chungking to Amoy/Taipei, and tin bars from Mengtze to Haifang (an operation that led to the capture of Bob Buol, later released). Major tonnage carried was rice, triple bagged, dropped over towns and missions that were surrounded, under siege and cut off from surface support.

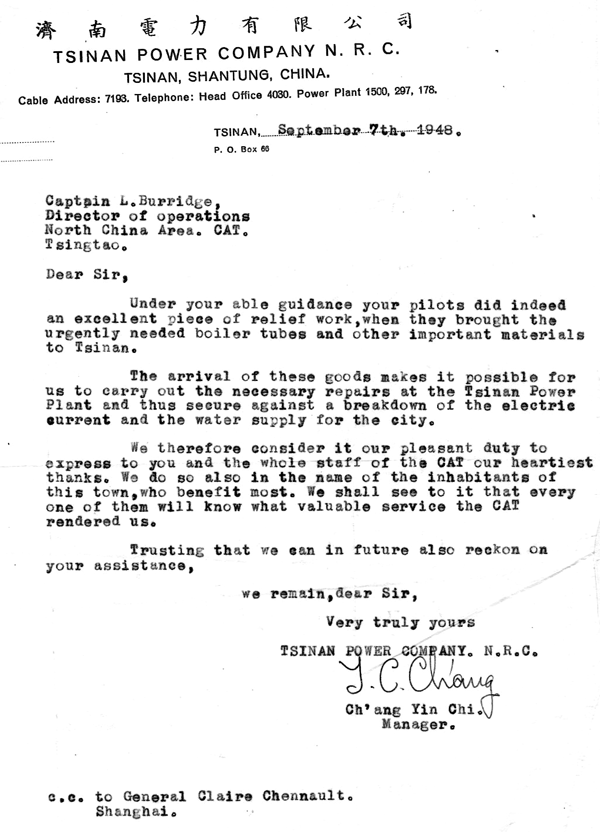

In addition to endless requests, CAT received countless letters complimenting it’s crews and personnel on the many critical services they rendered in desperate situations. An example follows.

The Wei Hsien Incident

After the loss of Manchuria and the withdrawal of General Marshal’s failed mission to promote a coalition government between Communist leader Mao and Nationalist President Chiang Kai Shek, hostilities resumed. The Reds had used the truce period to replenish their forces and resupply with military materials provided by Russia from stores in Manchuria.

Nationalist General Fu Tso Yi surrendered Peiping when his supplies were exhausted and no support come from the U.S. (as he anticipated) or from Nationalist headquarters in Nanking due to the influence of high ranking officers later found to have been under Mao’s control.

The Red push south to capture Shanghai and Nanking faced three strongholds isolated but heavily defended – each in a critical location to impede a Red victory: Wei Hsien at the railroad hub to South, East and West; Taiyuan, the largest industrial city in the Northwest; and Xuzhou, the gateway to the Yangtse river and Shanghai.

Wei Hsien, the first major target of the Red move south, had been supported by CAT airlifts from Tsingtao since surface transportation was cut off by the Reds, CAT (as CNRRA Air Transport) first flew in U.N. relief supplies and food, medical and communication materials. Later increased flights flew passengers, mail and commercial goods, both directions, including its substantial exports of tobacco.

The city thrived off this support, and very close relationships were formed between CAT Area Manager, Lew Burridge and staff, and Wei Hsien Garrison General Chang Tien Tso.

CAT’s Northern Area Headquarters was located at Tsingtao’s Tsan Kou Airport, which it shared with the U.S. Marines – a unit under the 7th Fleet Group at Tsingtao’s port. It was the former “home” of Burridge and CAT’s other U.S. Marine pilots. The CAT group was close to their Marine counterparts and shared some facilities, though Marine involvement in support operations was under diplomatic restrictions.

CAT’s Tsingtao operation was breaking all carriage records when his Wei Hsien Manager, Victor Chang, radioed Burridge that his staff was nervous and apprehensive about rumors of Red activity near the city. Burridge discussed these concerns with the U.S. Naval and Marine commands, the U.S. Consul General and General Ting Shi Pan, commander at Tsingtao. None could confirm or deny the seriousness of the reports. Burridge decided to fly to Wei Hsien to meet with the local Nationalist commander, General Chang Tien Tso and Presbyterian medical missionaries who were residing outside the city serving a substantial clientele throughout the country – often the most reliable information source.

Taking John Plank as co-pilot and Edwin Trout to return the C-46 to avoid an overnight stay, they landed safely to a quiet scene and were invited to spend the night at the Presbyterian mission residence. After a fine dinner with a debriefing from Kirk West, Mission Head, they were told that the Reds were infiltrating the smaller towns well north of Wei Hsien but had seen no large movements yet.

About 4 AM, a mission staffer (later found to be a Red sympathizer) woke them with news that the mission was nearly surrounded and they should leave for the safety of the city walls ASAP. This advice was taken and the city gates opened to accept them with a warm welcome from General Chang Tien Tso. Information they had was relayed to General Chang, and he said he was confident he could hold the city. In the morning he provided a jeep and escort to take them to the airfield just as a CAT C-46 orbited overhead to pick them up. The plane came in, but as it touched down, ground fire peppered the runway, so the pilot continued his run and returned to Tsingtao, leaving Burridge and Plank behind.

The plane’s crew radioed their predicament to Tsingtao and to CAT’s Shanghai headquarters where CAT co-owner and Executive Vice President “Whitey” Willauer ordered a plane from Tsingtao to constantly orbit Wei Hsien to observe and report on ground activity. That night he was there himself to take command of rescue operations.

The walled city of Wei Hsien is divided into two parts, the East City and the West City. From the airfield the pilots rapidly returned to the relative safety of Wei Hsien and found General Chang waiting for them at the gate of the West City. Chang confirmed, reluctantly, that the airport had been occupied, but assured the two that he would get them out. After discussion it was decided to create a 400 foot airstrip inside the East City by extending a soccer field there from wall to wall. Within 12 hours this was done with the enthusiastic aid of the military and the residents.

Willauer observed all this activity from the air and began an attempt to locate suitable aircraft for landing on the tiny strip. He found that the Marines, aware of the situation, had left an unmarked Marine L-5, gassed up, near the CAT ramp at Tsingtao.

That morning Richard Kruske slipped the plane into the field. Willauer had ordered “first in, first out” so Burridge and mail was loaded in. On take-off, trying to avoid buildings ringing the strip, one wing hit a roof and they crashed, thankfully without injuries. Now there were three to be rescued . . . . . . Burridge, Plank and Kruske.

That night an attack begun by the Reds was disrupted by directing the landing lights removed from the L-5 onto Reds below the walls, backed up by Nationalist sharpshooters piling up the dead below. General Chang gave each CAT pilot a pistol saying . . . “don’t get caught!” as they walked the walls with him.

The next morning Edwin Trout flew in another L-5, but braked into the wall and broke a propeller. However, a replacement prop was para-dropped that afternoon. Attacks were intense that night until the air seemed shrill with the sound of falling bombs. Then all Red attacks stopped – Willauer and his team led by Bob Rousselot, in orbit above, had dropped tons of empty beer bottles, courtesy of the U.S. Marines.

The following morning Burridge and Kruske flew out safely in the repaired L-5. Then Rousselot brought in another L-5 to pick up Plank, but crashed without injury on take-off. Next M.J. Staynor flew the Cub in and picked up Trout. Staynor returned again in the Cub, but broke a prop on landing, which was replaced in three hours. Finally, Rousselot flew out in the repaired Cub, and Kruske flew in again in an L-5 and rescued Staynor.

Wei Hsien’s walls were pierced by Communist forces a few days later. CAT’s Chinese staff escaped the city safely on foot under the direction of Manager Victor Chang and secret help from the locals.

General Chang, determined to hold strong, led his men through attacks on both cities. He was finally reported killed – brutally, with seventy holes in his body. General Chang’s heroic stand, impressive even to the Reds who killed him, earned him a rarely permitted honorable burial.

The loss of Wei Hsien was a shock to Nationalist leaders in Nanking and led to talks for a “Tsingtao Plan,” but the immediate effect was the Red’s capture of Tsinan, the provincial capital and a massive regrouping by the Reds to attack Taiyuan – the last real Nationalist bastion in the North. These events will be covered in a future edition of the Bulletin.

The following are excerpts from two interesting commentaries on the Wei Hsien incident by Louise Willauer and Foreign Correspondent Norman Sklarowitz. The full text of these documents will be available at the reunion or by request. This story is also told in a number of books, including Felix Smith’s “China Pilot”.

Excerpt from a letter to CAT from Louise Willauer entitled “Louise Peeks at War”, April 20, 1948:

Weihsien is about eighty miles from Tsingtao. It lies on a railroad, but its importance is not because of the railroad, but because of the roads which lead back into the Communist territory from there and because it is opposite Port Arthur. If Weihsien falls the Russians can smuggle stuff ashore which will be carried back through Weihsien to supply the Chinese Communists in the whole area. . . The Communists want Weihsien badly. . . When Lew radioed about his predicament the pilots in Tsingtao organized a rescue. Because the space for landing inside the city was so small, seven light planes were cracked up before all the Americans were brought out. . . Weihsien is really two cities, the East city and the West city, on either side of a river each surrounded by as separate wall. The airport was outside of the cities. The first landing strip which they picked within the walls was a small one in the West city. One of the pilots tried to go in in an L-5 and demolished the plane although he was not hurt himself. That left three Americans in there instead of just two, so they gaily radioed out, “Please send us a fourth for bridge!” The next night when there were four in there they said, “Thanks, now please drop us a pack of cards!” – – – which we did!

Excerpt from a draft of an article by Norman Sklarowitz, Pacific Stars and Stripes:

The little planes just barely clears the walls. But they did clear – and that was all anyone cared about . . . On the last run, the men saw the Communist troops remassing below. There would be no stopping them. There wasn’t. From the villagers who slipped through the battle lines a couple of days later, Lew pieced together the story of Weihsien’s last hours. They weren’t pleasant. An estimated 4,500 Nationalist troops died in the siege. When the Reds stormed the walls in the last attack, general Chang let a group of fourteen officers in an attempt to regroup. Communist machine guns cut him down. There were 70 bullet holes in his riddled body. Yet even the enemy recognized his gallant stand. Chang was buried with the dignity befitting a brave soldier.

With the fall of Weihsien on April 16, 1948, the way was open for the communists to consolidate their forces for the takeover of North and Northeastern China, taking Tsinan on July, 15th, Chinchow on July 26th, Paotow on October 23rd, Mukden on November 1st, Peiping on January 1st, and Tientsin and Hsuchow on January 15th,.

During that period, CAT launched it’s largest airlift operation from Tsingtao and Shanghai into Taiyuan, the capital of Shansi Provence, in support of Governor Marshal Yen Hsi Shan. Yen had proven to be an effective opponent of communist aggression as well as one of the most successful and most admired economic developers. His personal history identifies his passions and explains why he became a close friend of Lew Burridge and Joe Rosbert (both recorded numerous interviews with Yen, before and after he became Premier of China).

Yen was born in 1883 in Hobien Village, Shansi Provence, in a farmer/merchant family. He helped his father, Su Tong, in the family’s businesses where he experienced the faults of the Ching Government and the effect of corruption on his country.

When he was only twelve years old, he fought such unfairness and was elected village leader. In 1900, during the Boxer Rebellion, he organized resistance to German forces and saved his village from occupation.

At nineteen, he entered the military school in Taiyuan. Graduating in three years, he was then sent to Japan by his Government for five years in Japan’s military academy. It was there that he met Dr. Sun Yat Sen, and secretly joined Sun’s “Tung Mong Huei” movement to overthrow China’s oppressive Government.

In 1909, Sun Yat Sen ordered Yen to return to China to organize support in China’s Northern region from his Shansi base. He brought explosive bombs on his return and taught at the Shansi Military Academy.

He was given the option to remain loyal to the Ching Government or join Yuan Shi Kai’s opposition group. (Yuan’s son, Henry Yuan was a CAT executive). Yen chose to take an independent course and formed a new army in two provinces to stop Yuan Shi Kai from going North, but Yen’s commander, General Wu, was assassinated and Yuan Shi Kai took control of Peking declaring himself China’s President.

With Yen’s help, Sun Yat Sen overthrew Yuan’s forces. China was then declared a Republic by Sun and Yen returned to Shansi as Commander-in-Chief.

In 1912, Yen became Shansi’s Civil Governor. In 1914, he was also appointed a first degree general.

From 1916 t0 1925, his forces in Shansi were surrounded by avaricious warlords. He countered their threats by developing and implementing effective village governments to safeguard the interests and needs of their people, titled the “six plans” and the “three affairs”. His success in Shansi became a national model.

In 1920, 10,000 Chinese merchants who had been driven out of Soviet Russia returned to Shansi. They recounted the terror and cruelty of the Soviet regime. This led Yen to convene local meetings to explore ways to improve the social systems then in place in Shansi.

In 1923, he was appointed Vice-Commander-in-Chief of the Army, Navy and Air Force. In 1929, he was appointed Chairman of the Committee for Mongolia and Tibet Affairs.

In 1924, President Sun Yat Sen visited Yen with a plan to incorporate most of Yen’s reforms. National implementation, however, was delayed due to Sun’s sudden death. He was succeeded by Chiang Kai-Shek.

In 1927, President Chiang Kai-Shek led his armies northward against the warlords to consolidate his control. Yen joined in this effort by Chiang to unify the country.

Yen was elected to Chiang’s Central Executive Committee, the Kuomintang (KMT), Commander-in-Chief of the 3rd Group Army, Chairman of the Taiyuan Political Council, Garrison Commander of Peiping and Tientsin and a Minister of the National Government.

In 1931, he started a collective “village ownership of farm land” program, an “all manufacturing enterprises to be owned by all the people” program, and a ten year construction plan to create infrastructure essential for productive enterprises.

In 1932, Yen wrote his book “Product Certificate and Product According to Labor”. Chiang Kai-Shek was given this book when he visited Yen in 1935 and reproduced it for general reading by his staff which resulted in a number of initiatives to improve the image of the KMT Government.

In 1935, the Chinese communists forces fled from Kiangsi to North Shensi Provence (adjacent to Yen’s Shansi).

In 1936, Mao’s forces in Shensi attacked Shansi, and were defeated by Yen’s army. Yen’s village forces had been organized to defend themselves so that in less than two months the communists were forced out of Shansi.

In the same year, Japan attacked China. Yen held Shansi against Japanese attacks and maintained a “truce” with Mao forces while both opposed Japanese movements near Shansi/Shensi. With the war ending in August of 1945, Yen began a reconstruction program to restore and increase the industrial base of Taiyuan.

In 1946, CAT was asked to play a critical role in Taiyuan’s economic survival. As one of China’s largest industrial complexes in 1948-49, Taiyuan was dependant on material imports to compliment its locally produced raw materials essential to production. Yen had established an import/export company operating out of Shanghai to provide these needs. But as surface transportation disappeared, airlift support was critical. Due to the great diversity of materials involved—basic copper rods, printing inks, industrial controls, chemicals and paper to fly inward and finished commercial products exported outward forced a very flexible configuration of cargo space. As Taiyuan’s free perimeter was lost, cargo’s inward became life saving shipments of rice and medical supplies.

Yen’s resources were dwindling and requests for material and military support went unanswered in 1949, leading him to requesting flights to Nanking to make a personal plea to the Government for support. John Plank was assigned to meet this request while reasonably safe landings in Taiyuan were possible.

John Plank flew Marshal Yen Hsi Shan to Nanking on April 18, 1949. The next day Taiyuan came under massive attack causing Yen to request an immediate return to lead the defense even if landing there was impossible, in which case he would parachute in. After conferring with Chennault, Burridge refused his request injuring, temporarily, their close relationship.

Yen despaired but a few days and then responded to pressures from many in and out of Government to give them leadership as Nanking was threatened both by Mao’s forces outside and turncoats inside the city. With President Chiang Kai-Shek in Taiwan and Vice President Li Tseng Jen in the USA, Yen felt he could not refuse any help he could give to those still willing to fight for their freedom from a red takeover. He accepted the roll of Premier and quickly pulled the remnants of Government and the private sector behind alternatives still open for effective action.

Canton, Kunming, Chungking, Chengdu, Hainan and Taiwan were all under consideration as Headquarters for a final stand. Many business organizations and Government offices had already selected one or more of these alternatives after the fall of Tsingtao, Hsuchow and before the fall of Shanghai and Nanking. The Government was moved from Nanking to Canton on April 24, 1949, followed by CAT Headquarters.

CAT itself had installed its maintenance facilities on an LST and barge, which were moved to Canton from Shanghai in March with Captain Felix Smith as navigator.

As conditions worsened Chennault and Willauer struggled to keep the airline alive, in business and supportive of every remaining effort to continue an operative Government on the mainland of China.

As a supplement to this history overview of CAT operations, we recommend reading Felix Smith’s book “China Pilot” for many interesting anecdotes and personal recollections of pleasures and tribulations experienced during CAT’s very diversified operations. “China Pilot” was selected by the Smithsonian as a scholarly work, and remains in print. You can contact Felix directly at venus747@ymail.com or (262) 827-4095 for an autographed hardcopy (best option), or go to www.amazon.com.

CAT’s role in the Korean War was substantial. On the pre-dawn morning of Sunday, June 25, 1950, Russian T34 tanks, operated by the North Korean People’s Army, crossed Latitude 38. Within three days the enemy overran Seoul. Hordes of civilian refugees and retreating soldiers of South Korea’s army died when the steel bridge crossing the Han River south of the capital was prematurely blown up by its own army. The strategy had been to blow the bridge after the South Korean Army had crossed and before the North Korean People’s Army reached it. However, the costly destruction of the bridge didn’t stop the enemy, their tanks and troops used the nearby railway bridge.

General MacArthur’s 24th Infantry Division, soft from occupation duty in Japan, armed with light weapons, were no match for Russian tanks. They suffered a 50% casualty rate as the enemy pushed them toward Korea’s south coast, to the embattled Pusan Perimeter. President Truman mobilized military reservists and the National Guard.

CAT borrowed additional C-46s from the Chinese Air Force to transport supplies to the battleground near Pusan. We landed on short PSPs (pierced steel planks) and returned to Japan with wounded, many of them young soldiers who had been living it up in Japan, believing that America’s wars were behind them. Enemy drivers tied ropes to American wounded and towed them over the ground until they died. Our crews flew as much as 20 hours a day / 150 hours a month, grabbing sleep via the hot -bunk system in a Tachikawa warehouse. General Tunner, director of the WWII Himalayan Hump and subsequent Berlin Airlift, conducted the combo USAF / CAT airlift in these early days of the United Nations “Police Action.”

Finger-pointing blame wasn’t a monopoly of Korea. American journalists, briefed by “unnamed senators,” called the surprise invasion a shocking failure of American intelligence. But Major Jack Singlaub, known for his impeccable honesty, investigating the details for Intelligence Director Admiral Roscoe Hilenkoetter, found that Secretary of State Dean Acheson, President Truman’s foreign policy advisers and General MacArthur’s staff, particularly the imperious Major General Willoughby, had received written warning of an imminent invasion five days before it occurred. Signatures signifying acceptance of the warnings were declared forgeries by Senator McKeller, but nobody believed him.

CAT could have added fuel to the flames, but we stayed mum. Fifteen of our passengers — Korean manufacturers on a sales junket throughout Asia — had progressed as far as Sydney, Australia, next stop, New Zealand, but they asked co-captains Harry Cockrell and Felix Smith to cancel the trip and return to Seoul immediately. Letters from home begged them to return because war was imminent. Their adviser on board, the Commercial Attaché of the American Embassy in Seoul, told them to proceed to New Zealand as scheduled, the rumor of war was nonsense. The passengers were astonished when the pilots ignored their fellow American and headed north for Korea. It was an easy decision. The passengers had paid for the charter, they had rights. One or two days after they landed at Seoul, the war began.

After General MacArthur’s brilliant and daring attack from the sea in the tidal area of Inchon, he captured the North Korean capital of Pyongyang and proceed north to the Chosin Reservoir area North Korea. During the distribution of Thanksgiving rations, MacArthur assured his troops they’d be home for Christmas. A laconic colonel jibed, “If you smell Chinese food, retreat.” On November 28, Chinese soldiers who had infiltrated and hidden in north Korea’s mountains, arose in a surprise night attack which led to the historic evacuation of North Korea’s Chosin Reservoir district in the sub-zero cold of Korea’s winter. General Mathew Ridgeway equated Supreme Commander MacArthur’s blind confidence with that of General Custer of America’s Indian wars in the wild west. Months before Korea, General Chennault, in an informal discussion with two CAT pilots said his friends in South China had warned him that many soldiers, having defected to Chairman Mao, marched north by night and slept during the day, possible destination North Korea.

CAT’s safety record was so well known, war correspondents preferred to ride with us. They said we left our mistakes in China, we were like mongrel dogs who knew how to cross a busy street without getting hit. However, on December 8, Paul DuPree, a captain new to Asia, attempted to penetrate low clouds on Korea’s east-coast port of Yonpo to evacuate wounded soldiers. The USAF precision radar approach unit had been set up but not yet calibrated. He crashed and the crew survived with slight injuries, but a medic from the 801 Air Evacuation Squadron was killed.

The next night, Robert Heising, an experienced captain but also new to Asia, departed Tokyo with an as-signed cruising altitude of 8,000 feet. USAF Air Traffic Controllers saw his radar image head toward the 12,388 foot Mt. Fuji. They used multiple radio frequencies in a frantic attempt to warn him, but Heising didn’t respond. When the weather cleared, a search and rescue plane found the wreckage on Mt. Fuji’s slope at precisely 8,000 feet. A small, tight low-pressure area generating 90 knot winds — an anomaly undetected by weather forecasters — had formed off the south coast of Japan, and a CAT captain, inbound at that hour, reported snow static which interferes with aircraft radio direction finders. Since Oshima Island’s radio beacon was the check point and signal that it was safe to turn west, and snow static could have caused Heising’s direction finder to meander instead of presenting a positive line of position, his DR (deduced reckoning) navigation, utilizing forecasted winds, could have put him on his short course to Japan’s legendary mountain. In those days it was that kind of navigation in Asia.

Our passenger routes throughout Asia continued, but our principal work was the transport of battle supplies and return of wounded; and CIA missions which included the parachuting of Chinese spies on the Mainland of China. Although most of these courageous Nationalists were captured and executed, the uncertain time, place and purpose of the incursions confined Red Chinese to home guard who otherwise could confront United Nation troops in Korea. Severe as the Cold War seemed in those years, the worst was yet to come.

(Bibliography: Hazardous Duty, by Major General John K. Singlaub, Summit Books, 1991)

1950 was the year of many changes. North Korea’s attack on South Korea was noted in the previous edition of the Bulletin, but recently declassified CIA documents reveal an interesting clash between Generals Claire Chennault and Douglas MacArthur. It warrants a flashback.

When news of the invasion reached CAT’s headquarters in Hong Kong, CIA officer Al Cox met with Gen. Chennault at Kaitak Airport at 7 a.m. “A cable signed by Chennault was sent to MacArthur offering immediately the full use of all CAT facilities in fighting the North Koreans. General MacArthur replied several days later that the offer was appreciated, but adequate airlift was on hand to cope with the situation.”

Chennault and Whiting Willauer were incredulous. They dispatched Joe Rosbert and Lew Burridge to Tokyo to ensure that the Far East Air Force (FEAF) was aware of CAT’s capabilities. Told that FEAF didn’t have enough fork lifts or refueling tankers to sup-port CAT, Joe and Lew described, as only they could, how we surmounted these challenges in China; but MacArthur’s decision prevailed.

Seven weeks later, “Willauer and Cox were asked to come to Tokyo as rapidly as possible. En-route to Tokyo they stopped at Taipei to pick up Rosbert and Rousselot. Senior officers of FEAF told Willauer that they urgently required every bit of airlift CAT could provide.

The urgency was so great that they told him to prepare an estimate on which a contract could be based as soon as possible and, if necessary it would be readjusted at a later date. FEAF advised that they would provide fuel; spare parts, as required and if available would be provided from Air Force stocks; every assistance possible would be given in the maintenance of the aircraft; the CAT airlift would be based at Tachikawa (a FEAF air base); facilities for CAT crews including PX and Commissary would be provided by the Air Force, but they could not furnish billeting. It was somewhat disturbing to CAT personnel involved when the Air Force quietly advised that things would go more smoothly if Chennault did not come to Tokyo, at least at that time. It was apparent that General MacArthur did not want to welcome any other stars to his firmament.

After some hurried calculation, taking figures out of the air but based on CAT experience, a contract was drawn up. On August 25, the Air Force indicated that the contract was acceptable and that they could use every bit of airlift that was made available.

Cables had gone out to all the air crews and some of the American maintenance personnel who had been placed on leave without pay to ascertain whether they were still available and willing to return to the Far East. A surprising number quickly responded. On September 8, the Far East Air Material Command (FEAMCOM) and General MacArthur approved the contract.”

CAT met the requirement for air crew billets at the FEAF air base by placing about 50 army cots in a warehouse. Sometimes we didn’t get back to Tachikawa for several days. Names of returning airmen were recorded at the bottom of an Air Force expediter’s clipboard while outbound replacements were taken from the top. On occasion it took only two hours to ascend from the bottom to the top. Until we got sufficient airmen, we sometimes flew for 20 hours, grabbed a couple of hours sleep and went out again. It was the hot bunk system. We flopped on which ever cot was empty and slept in our clothes.

“Within less than two months, CAT had rebuilt its capabilities from 400 hours per month to 4,000 hours.” We transported medical supplies, machine gun and small arms bullets, hand grenades, mortar shells, napalm tanks & mix, aircraft engines, spare parts, gasoline, barbed wire and returned to western Japan’s Itazuki Airport with wounded where ambulances waited to carry them to the U.S. Army hospital in Fukuoka.

The first CIA officer to appear was WWII OSS veteran Alfred Cox who had developed small operational groups (OGs) of highly trained men to parachute into Nazi occupied France where they contacted local resistance groups and wreaked havoc. Historian William Leary wrote, in Perilous Missions, “Before the invasion of Europe, Cox jumped into the Rhone Valley where his units destroyed bridges and power lines, set up road blocks and ambushed enemy columns. Combined OG Marquis forces killed 461 Germans and captured 10, 021 at a cost of five Americans dead and 23 injured or wounded. It was the first real use of the American Army of organized guerrillas of highly trained bilingual officers and soldiers who operated behind enemy lines.”

One of Al Cox’s officers — Conrad La Gueux — had the appearance of a bright college student, but he was a battle-seasoned, decorated Army captain who had jumped into France as leader of an OG group. The third CIA officer to join us — John Mason — had been a regimental commander with the 90th Infantry Division in WW2 Europe. His decorations included the Distinguished Service Cross, two Silver Stars, three Bronze stars, two Purple Hearts.

Hans Tofte, an OSS veteran of paramilitary operations, with Major Julian Niemczyk, chief of Escape and Evasion (E&E) established a network for downed military pilots. CAT placed a number of C-46’s and one C-47, at Tachikawa for their operation. Hans, a Danish American, first saw Korea at age 19, working for The East Asia company, a Danish shipping firm. He became fluent in Korean and several other languages. Decades later, this skill enabled him to organize sympathetic North and South Koreans, fishing boats, lookout stations, communications equipment at 20-mile intervals along the entire coast of north and south Korea with a cover which was easy to believe. They posed as a black market network. When Hans advised General MacArthur’s Colonel Charles Willoughby that he would acquire gold bars for military airmen to pay friendly Koreans for help if they were shot down, Willoughby vetoed the purchase because it violated restrictions on foreign exchange. But Hans Tofte flew to Taipei and returned to Tachikawa with $700,000 in one-ounce gold bars, much to the delight of our boss, Bob Rousselot who said, “Hans knows how to get things done.”

After MacArthur’s daring assault across the mud flats to Inchon on September 15, 1950, his capture of Pyongyang on October 17, and his November Thanksgiving season announcement that his soldiers would be home by Christmas, he discounted unconfirmed reports of Chinese soldiers in Korea. At times he referred to them as an Asian mob, while Major Charles Willoughby said, even if the Chinese were in Korea they should not be taken seriously. However, historian Joseph C. Goulden recorded in his brilliant book, “Korea”, that five Chinese armies totaling about 100,000 soldiers confronted MacArthur’s Eighth Army and the ROK II Corps, and American intelligence officers reported that they showed excellent fire fight discipline, especially at night.

The Chinese surprise awakened the Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) to the fact that CAT was an essential component of America’s military capacity in Asia.

“Flying more than 15,000 BOOKLIFT missions, CAT transported 27,000 tons of cargo and mail and thousands of wounded. “

General William Tunner, director of the WW2 Himalayan Hump, Berlin and Korean airlifts, reported, “At a time when air transportation was critically short, you made available to us your aircraft and your trained personnel in the quantities required . . . CAT did an outstanding job.”

The CIA, acknowledging that CAT has shuttled hundreds of guerillas and agents between CIA training and staging camps, reported, “CIA could never have accomplished our outstanding record in the early days of the Korean War without CAT.”

Hans V, Tofte told historian Bill Leary that he considered CAT “absolutely invaluable” during the early phase of the Korean war.

High ranking military officers knew that CAT was entirely owned by the U.S. Government and operated by the CIA, but most of us believed the myth that CAT was a contract carrier and the CIA was one of our customers. Scheduled passenger routes, flight attendants and commercial charters were covers which hid the secret.

The pressure of the Korean War was relieved by “Operation Paper” which supported Chinese Nationalist General Li Mi. In the closing days of China’s Civil War, General Li and his 1,500 men had fled across Yunan’s border to the protective hills of Burma, about 80 miles from Thailand.

Stragglers followed and joined Li which eventually increased his rogue army to 4,000 soldiers, albeit poorly equipped, and living off the country. About five times a week CAT parachuted food and supplies to Li. China’s entry to the Korean War had alerted America’s chiefs of staff. They were concerned about an attack on Hong Kong or Taiwan. Li Mi’s incursions could preoccupy Red China’s military commanders.

Red China’s East Coast was harassed by Western Enterprises Incorporated (WEI), of the CIA’s Office of Policy Coordination (OPC), formerly the secret paramilitary arm of the CIA; and CAT furnished the transportation in PBYs flown by Connie Siegrist, Don Teeters, Red Kerns with crewmen Cyril (Pinky) Pinkava, Ted Matsis and others. Troops who would otherwise fight in Korea were held on the Mainland, on home guard, wary of spies which CAT dropped at diverse and unpredictable places and time.

CAT’s participation in the Cold War had only started.

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

“Perilous Missions”, William M. Leary, Smithsonian Institution Press, 2002

“Korea: The Untold Story of the War”, by Joseph C. Goulden, McGraw Hill, 1982

CIA Documents by Alfred T. Cox

On November 28, 1950, less than a week after Thanksgiving Day, Communist China launched its surprise attack on United Nations troops. Red soldiers in overwhelming numbers arose from their hiding places in mountains of the Chosin Reservoir area. A Turkish unit, the U.S. Army’s X Corps and First Marine Division fought their way to the Coast at Yonpo in an 18-day horrendous march in sub-zero temperatures. The X Corps casualties aren’t known, but the First Marine Division endured 604 KIAs and 192 MIAs. Eight Marine pilots were killed, 4 missing, 3 wounded . . . The Chinese suffered 15,000 KIAs.

The Far East Air Force (FEAF) asked CAT for 28 planes with crews. Director of Operations, Joe Rosbert readily agreed. That was CAT. Think positive, commit boldly and then figure out how to get the job done. We rented C-46s from the Chinese Air Force, payable in advance, but only two were airworthy. Chief Pilot Rousselot rushed to Manila to negotiate the lease of five C-47s from Trans Asiatic Airways, including crews. One of its pilots, Director of Operations Monson (Bill) Shaver, remained with CAT/Air America for the following 25 years and became Chief Pilot of PARU, the Thai parachute police.

The former Lutheran Mission C-47 named St. Paul, now a one-airplane airline (International Air Transport) also joined the CAT fleet, along with its captain, Bill Dudding, a WW2 CNAC veteran; and copilot—flight engineer—radio operator—mechanic Max Springweiler, an old China Hand, having joined Eurasia, (Lufthansa’s China subsidiary) in the mid-1930s. When the Commies chased the missionaries out of China, they gave Bill and Max the airplane in lieu of salary owed. Max’s presence made CAT globally sophisticated by serving as Manager, Long-Range Charters. Whenever an intelligent, courteous European who spoke passable French and Chinese in addition to fluent English and German was needed to resolve a sensitive issue, he became our “fixer,” particularly in Indochina where officers of the defeated Nazis had joined the French Army.

The balance of the 28 A/C fleet was reached, courtesy of General Chennault who used his influence to borrow them from the USAF.

Other seasoned CNAC pilots who came to CAT at that crucial time were first assigned to Operation Squaw-Two. They were Don Bussart, Steve Kusak, Hugh Hicks (who became one of the CAT Chief pilots), and Tom Sailer (who became Chief Pilot, Southern Air Transport, one of the CAT/Air America A/C menagerie). Other newly hired pilots were Al Judkins, Maury Clough, and Ken Milan.

On Christmas Day, 1950, while we were engaged heavily in the Korean War, the CIA began an inroad into French Indochina with STEM, the Special Technical & Economic Mission. STEM distributed medical supplies directly to the Vietnamese with a CAT C-47 and crew that was attached to the American Embassy in Saigon. While CAT supported two wars operationally, American taxpayers paid the cost. Although the Korean “Police Action” was a joint United Nations operation, America paid 85% of the cost, which translated to Three Million Dollars a day. Americans also paid about 85% of the cost of France’s Indochina War.

While engaged in these two wars, CAT maintained a scheduled passenger and cargo service: Seoul, Tokyo, Osaka, Naha, Taipei, Hong Kong, Bangkok, and eventually Manila; and “Round the Island” domestic service: Taipei, Taichung, Makung (one of the Pescadores Islands), Tainan, Taitung, and Hwalien. We also began negotiations for the initial operation of Korean Airlines. With Northwest and other airlines outside Japan, we found a way to provide that country with domestic air service which circumvented the terms of surrender which prohibited Japan from operating aircraft. Lew Burridge with his imagination and easy-going manner was a major principal in the success of this operation. We also operated a successful New Zealand domestic air service for four months. At the same time our leaflet and spy drops over the China mainland continued. Captain Bill Welk, a WW2 veteran with experience in the B-17 Flying Fortress, made incursions deep into China dropping spies and leaflets as distant as the Gobi Desert. Captains Eddie Sims, Doc Johnson and Allen Pope were also more heavily engaged in these flights than the rest of us.

But most of us shared the flying in Laos which levied a large number of KIAs.

Our greatest agony at that time was the harassment from CIA visitors who criticized CAT’s management style with a misunderstanding that belied our achievements. The principal thorn in the CIA’s side was the slack chain of command between Washington, DC. and Taipei which the CIA tightened, thus squelching the autonomy of our far-flung Area Managers. Whitey objected vigorously, declaring, “We have created a spirit and an intense interest in the affairs of CAT which is probably its greatest asset.” CIA inspectors also frustrated our first CIA stars, Al Cox and John Mason, who needed to make decisions without waiting for approval from Washington, DC.

Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal, two Gold Stars), with a home in Louisville, Kentucky, reported to Tachikawa Air Base, Japan. Also reporting was Captain Bob Snoddy, 31-year-old Lt. S.G., USN, during WW2 (Air Medal, four Stars, one Purple Heart, with a record of shooting down two enemy aircraft), who expected to be a father within three weeks. His wife, Charlotte, like Bob was a native of Eugene, Oregon. Their mission: snatch a Chinese spy out of Kirin Province, Manchuria, Northeast China. CIA Historian, Dr. Nicholas Dujmovic, to his credit described the mission with meticulous honesty at one of our reunions. One of the CIA agents declared he had evidence that the request for the spy’s pick-up was an ambush. A superior officer ordered him to keep his mouth shut. He kept mum and later regretted it painfully. Schwartz and Snoddy were killed in the shoot-down. A forearm bone identified as Snoddy’s was recovered more than half a century later. JPAC still searches for the remains of Schwartz.

The CIA’s Deputy Director, General Charles Cabell, a graduate of the U.S. Military Academy, asked his Army Air Corp fellow officer, George Doole, to impose order on the Agency’s adopted orphan. General Chennault was tucked safely out of the way as Vice Chairman of the CAT Board of Directors. Vice President, Operations, Flying Tiger Ace Joe Rosbert was provided a luxurious office by Taipei standards, a limousine with driver, but nothing to do. Lew Burridge, trivialized by George Doole, accepted a position as President, North Asia, of one of America’s largest pharmaceutical corporations. Marvin Plake, CAT’s Director of Public Relations, had been the Naval Intelligence officer during WW2 with Chennault, coordinating the 14th Air Force raids on enemy shipping off the coast of China, accepted an offer to become the head of the Pacific Travel Association.

The turmoil subsided with the distraction of Squaw-One, which was CAT’s first operation under the wing of the French Air Force C-119 Flying Boxcars loaned by the USAF. They were re-painted with the French Air Force insignia and rushed to Hanoi. Named Squaw-One, CAT pilots first received notice on May Day, 1953.

May Day, 1953. We pilots with the day off in Tokyo received an urgent message from Tachikawa Air Base, “Report immediately with clothes for two weeks in a hot climate…Come by train, the road is clogged with Communist demonstrators.”

At Tachikawa our C-46 waited on the tarmac. No cargo, no passengers, except for a few “day off” pilots- Bill Shaver, Eddie Sims, Harold Wells, Steve Kusak, and Gene Porter. Ops designated me the worker-bee, so I began the pre-flight check. The duty operations manager, clipboard in hand joined me under the wing so I could sign off the weight and balance document. The flight plan was missing. “Where are we going?” I asked. He said he couldn’t tell me. “If I get the monster into the air I gotta know which way to point it,” I said. Shielding his mouth with his hand like a coach to his quarterback in the Super Bowl, he said, “File for Taipei, but when you exit Japan’s F.I.R. (Flight Information Region) re-file for Clark.” (An American air base 50 miles north of Manila.) But after we left Japan’s region we got an ops message from Taipei ordering us to land in Taipei after all. “The Chief”, Bob Rousselot, a WWII Marine Corps veteran, met us and eventually climbed aboard with several more “day off” pilots he had corralled in Taipei – Bill Welk, Paul Holden, and Gene Bable. En-route to Clark Base, Rousselot employed his famous gimlet-eye frown and said, “What you’ll be doing is very important – don’t relax discipline just because you’re a long way from Taipei.”

It was dark, the end of the day when we landed at Clark. An Air Force “Follow Me” jeep led us to the tarmac and a bird colonel, the base commander, immediately boarded and welcomed us, adding, “It’s my understanding we’ll check your men out on the 119 . . . how much time do we have?” “Three days,” said Rousselot. The colonel said, “We can’t check pilots out in three days.” Rousselot glanced at his wrist watch and said, “You’ve wasted five minutes already, let’s get going,” but he immediately calmed down to say, “Porter here is our least experienced pilot and he logged seven thousand hours. These other guys have considerably more experience.” The Colonel said, “Follow me,” and we all walked toward a Quonset hut under a palm tree while Bill Shaver whispered, “Nobody intimidates our Chief.”

An Air Force master sergeant hurried to the hut to unlock the door and turn on the lights, and we said “Wow.” The Quonset hut was full but neat with chairs, chalk board, movie screen and many colored mock-ups of the C-119 Flying Boxcar systems – electrical, hydraulic, pneumatic, fuel, flight controls. Such sheer luxury we had never seen.

By now it was about 9:00 P.M. The school began immediately. The master sergeant, obviously an old-timer, told us, “The C-119 has two Pratt & Whitney 36 cylinder corn cob engines and a landing gear held together with tissue paper.” (When we saw the fuselage vibrating when the engines idled, we believed it.) “No one has yet ditched one successfully,” he said. “Don’t attempt a belly landing. The floor will curl up below you and you’re dead. In an emergency, land with the landing gear extended.” He was a no-nonsense, practical, straight-talking jewel, who knew how to talk to pilots.

After a brief night of sleep we saw many young Second Lieutenants on the flight line, waiting for their assigned planes to show up. When a C-119 Boxcar with the concentric red white and blue circles of the French Air Force taxied to the flight line, Captain Jack DeTours, our flight instructor said, “There’s our bird.” Jack DeTours was one of the best instructors I ever had. I wondered if the USAF Training Command hand-picked its teachers.

With the engines at take-off power, it felt like we were catapulted into the air. After the customary “get acquainted” maneuvers – slow flight, steep turns, approach to stalls – with various slap settings, we were loaded with bags for practice drops and a voice in the Air Force control tower coached us step by step to the target. “Climb to five hundred feet, right 90 degree turn and continue to now thousand, slow to–”. I thought, just show us the target, we’ve done this time and again in China, but I kept my mouth shut.

We were surprised when one of the USAF C-119s, empty, with all that power, experienced an actual engine failure and headed back to the base while our instructor and others on the radio encouraged, “Come on, you can make it.” They genuinely sweated him out. It was then we realized that we had experienced so many engine failures in China, in thunderstorms and black nights with few navigation aids, that the loss of an engine on an empty cargo airplane in good weather and daylight is a gift. We had a lot of know-how under our belts that these young guys had yet to experience.

It was May 5, 1953, by the time we headed for Hanoi. By then we knew our mission. The City of Na Sam, the largest French fortress in northern Indochina was under siege. Communist rebel shells had dropped on Moroccan and Lao troops with unexpected accuracy. The Vietminh rebels used water buffaloes as living bulldozers to push the barbed wire barriers aside.

Seven thousand Vietminh surrounded the strategic city, which lay west of Hanoi. The French-held ground was called an awful bloody mess. We CAT guys were hyped up. It seemed like China again.

The USAF dispatched us to Hanoi via Tourane for fuel. We were heavily weighted with spare parts and carts of drinking water along with a maintenance master sergeant and six USAF mechanics. The French Air Force base at Tourane, with its palm trees and gentle sea breeze and a scent of flowers, reminded us of Hawaii.

The refueling tankers were idle, without drivers, parked for the night. Officers were off-base preparing for a gala outdoor Spring Festival. Told we’d be refueled “tomorrow,” I asked, “Where’s the Base Commander?” It was his day off, the evening of the Spring Festival approached. A French Air Force driver took me to the commander’s house in Tourane’s residential section. My knock on the door was answered by a teen-age Vietnamese house boy. “My master is sleeping,” he said. I said, “Wake him up, it’s important,” but the youngster hesitated in the doorway, trembling. “It’s alright,” I said. “Let him sleep.”

“Take me to the garden party,” I said. The officers and their ladies were welcoming Spring. Tables with white cloths and decorated by flowers occupied an outdoor area the size of half a football field. Colored paper lanterns swung on overhead wires. The gentle ocean breeze was refreshing. French ladies in summer gowns chatted cheerfully. Their escorts in starched white uniforms with epaulets, so it became apparent when I was directed to the proper officer, I looked at the highly decorated base commander. There, in sweaty khakis, the only way I could show respect was the doffing of my red baseball cap. “We’re at the airport prepared to parachute supplies to Na Sam,” I said. The commander, equally courteous said we’d have fuel in the morning. I left, feeling like the floor show of the evening, the specter at a feast.

We were refueled the next morning. Finally at Hanoi, we gathered in the French Air Force briefing room under the airport control tower. A chalk board indicated the “Sorties” for the day. The base commander at Hanoi greeted us as honored guests. “Welcome to the Anjou Squadron,” he said. His neat uniform, French accent and brush mustache gave him the appearance of Adolphe Menjou, the French-American movie idol of that era.

Amused and patronizing, he said he would be “charmed” by our questions. Steve Kusak asked about the instrument approach procedure in fog. Adolphe Menjou brought his fingernails to his nose and said, “You smell zee runway.” By now I should have caught on to the charade, but was slow enough to ask, “What’s your lost communications procedure?” Adolphe Menjou pointed his forefinger to his temple, cocked his thumb and said, “You zhoot yourself.” It felt like a Grade B Foreign Legion movie until someone brought me back to reality by shouting, “Wow, Rousselot ought to hear this.”

The French Air Force’s Flying Boxcar configuration was two CAT pilots with a French Air Force flight engineer, radio operator, and navigator. Our engineer happened to be a Russian, Sokolov – a congenial guy who had defected to France. After his switch, two men, obviously KGB, stood on the street watching his apartment window all night until Sokolov confronted them face to face, saying “I’m a Frenchman now, get the hell out of here or I’ll call the police!” They departed.

French fighter pilots provided flak suppression – they strafed the ground wherever they saw muzzle flashes, but they didn’t have to fire their weapons most of the time. The presence of the combat planes was enough to cause a cease-fire. The enemy knew that their muzzle flashes would give away their location. Most afternoons we had no protection because the fighter pilots drank wine with lunch and then took an afternoon nap.

A Dutch plantation owner said Americans were too gung-ho, they wanted to end wars immediately whereas savvy Europeans learned how to live with a war. He allowed his plantation workers days off if they wanted to fight for the Communists periodically; and it was easy for his company to bribe its way past enemy road blocks. But French citizens in Europe were fed-up with the long, fund-draining war and loss of their soldiers. Their Parliament recognized it and stopped drafting its citizens, relying on its colonial troops.

As in China’s Civil War, the rebels controlled the countryside while government forces held the cities.

Indochina. Spring/Summer, 1953. At the break of day, minesweepers traversed rural roads to detect land mines which might have been planted by Vietminh guerrillas during the night. They built mines from unexploded French shells found in old battlefields. Every several miles a blockhouse with a watch-tower and flag pole raised a globe the size of a basketball after that section of road had been cleared. The optimism of our Jeep drivers exceeded their knowledge of exploding shrapnel. They transported us to and from airports by flooring the accelerator and skidding on gravel bends in the road while frantically wrestling the steering wheel. I once shouted, “Why go so fast?” He took his eyes off the road, turned his head and hollered, “If hit mine it go off behind us.”

Bernard Fall, the prominent war correspondent, military historian and author of the classic “Street Without Joy”, hitched a ride with Steve Kusak and reported, “The plane goes into a shallow dive, and as we hit the Drop Zone, sharply noses upward. The two riggers, warned by the buzzer, jump up on the sides of the plane while the whole load in a roar of clanking metal and whooshing static lines leaves the plane in a few seconds… a slight tremor on the left wing and some holes appear in it, seeming out of nowhere. Communist flak. It’s an odd feeling for I’d never been in an airplane in a combat zone and feel so damn’ naked. The Boxcar, lightened of all its load, again climbs steeply.”

The French Air Force soon moved our operating base from Hanoi to Haiphong where we discovered that Adolph Menjou’s amused condescension was an anomaly. Gracious French Air Force and civilian folks made us honorary members of the Cercle Sportif clubs throughout Indochina: swimming pools surrounded by flower gardens, tennis courts, dining rooms with French and Vietnamese goodies. Gene Bable was the only CAT with the wit to pack his American country club 1953 swim suit. The guard eyed his attire which stretched from belly button to knees and said, “Nonsense, they are not for swimming, they are trousairs for tenees”. The rest of us in locally purchased French briefs explained our prudish pal’s missionary status and we all splashed in. Bill Welk said, “CAT always finds a way.”